19th Century printings of lithographs and etchings produced within early avant-garde communities.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

M. Adolphe, Un Galop infernal à la salle st. Honorée (An Infernal Gallop at St. Honoré Hall). Undated, c. 1836-37. Lithograph from unidentified magazine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

David d'Angers & Edmond Lechevallier-Chevignard, Medallion Portrait of Achille Devéria. (Undated, c.1845-1857) Intaglio; illustration from unknown book. With remains of an article on Devéria on reverse side, speaking of him as still living.

Engraving by Chevignard after the 1828 relief sculpture by d'Angers.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anonymous, Les Moines devoilés ou le jesuit Malagrida (

The Monks Unveiled or the Jesuit Malagrida). Undated, c.1830-1850. Etching.

This

anonymous print is part of the surge of anti-clericalism that was a

massive presence in the Left from the French Revolution until well into

the 19th Century. On one side, the movement intersected with a number of

progressive movements including free speech, anti-racism,

anti-imperialism, socialism and proto-anarchism, and the separation of

Church and State. On the other, it quickly became a driving force in a

slew of conspiracy theories from both Left- and Right-wing perspectives,

and often led to anti-Catholic persecution and fed into growing

nationalism and xenophobia in Protestant countries. The Jesuit order

was often considered the epitome of Catholic/Clerical abuse and

duplicity.

This print emphasizes

the humanitarian aspects of anti-clericalism, while still appealing to

more conservative monarchist sentiments. The central figure is labelled

as the powerful 18th Century Jesuit Gabriel Malagrida, who who was

implicated in a supposed plot on the life of King José I of Portugal, on

extremely flimsy evidence; here, he brandishes a manuscript entitled

"Hatred of Kings". To his left is Jacques Clémont, the ultra-Catholic

assassin of the religiously tolerant King Henry III of France; to his

right is unidentified. The bricks of the edifice around Malagrida are

inscribed

with the products that drove colonial conquest, including tobacco,

opium, gum arabic, pears, topaz, porcelain, etc. We see the Jesuit order

blamed, with varying degrees of legitimacy, for the destruction of

Native American cultures in the conquest and colonial exploitation of

Latin America, the enslavement of African and Native American people,

the persecution of

Heretics, and the overthrow and execution of six European kings.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

??? Benjamin, Portrait of Roger de Beauvoir. Undated, c.1840. Lithograph. Galerie de la Presse: Paris. Printed by Aubert. With embossed seal of Galerie de la Presse.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Louis Boulanger, Portrait of Victor Hugo. (1889 print of 1829 Etching). From

Le Monde Illustré. Mounted by 19th Century owner to back of an unidentified intaglio landscape, w/archival notes in pencil.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Louis Boulanger, Paganini in Prison. (Early 20th Century reprint 1831 image)

This

image was something of an icon in underground Romanticism, and a rather

controversial one. Paganini, the great violin virtuoso, was a major

figure and precursor of a 20th Century rock star, and dark rumours about

devil-worship, conspiracy, and mystery swirled around him (most, if not

all, unfounded). This made him a particularly intriguing figure for the

dark subcurrent of Frenetic Romanticism, as typified by Bouzingo group.

This print, in fact, was made by a co-founder of that group, Louis

Boulanger, and embroiled him in a public argument with Paganini himself,

who was shocked to find a crowd gathered around a print-shop window

discussing it, and he published an article asserting that he had never

been in prison, the story was apocryphal, and the picture libelous.

Boulanger, in turn, replied that he had been unaware of the truth or

falsehood of the claims, but considered the imprisonment of the artist a

fitting symbol for the tormented energy of Paganini's performances, and

that he was furthermore referencing Tasso's imprisonment. This is an

early 20th-Century reproduction of Boulanger's print.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A. C. (Unidentified), Le Cauchemar de la Poire (The Pear's Nightmare). "Caricatures politiques No. 45." Undated, c. 1833. Lithograph. L. de Becquet: Paris. Printed by Aubert.

As

democratic opposition to the "Liberal Monarchy" mounted in the wake of

the 1830 Revolution in France, political cartoonists became leaders of

the struggle in a constant, high-profile contest with the government

over censorship, especially those associated with the seminal satirical

journals Caricature and Charivari. The editor of both

journals, the cartoonist Charles Philipon, regularly portrayed King

Louis-Philippe as a man with the head of a pear, resulting in a public

court case in which he earned acquittal by giving the jury a

step-by-step demonstration of the process of artistic abstraction.

The

portrayal of "The Pear" quickly spread to other cartoonists of the

Left. This print deploys it in a delightfully weird example radical

propaganda typical of the Neo-Jacobin fringes of the Romanticist

movement. It parodies the already-famous gothic painting The Nightmare

by Fuseli, but the sleeping woman is replaced by King Pear, while the

crouching demon is now Lady Liberty, wearing the phrygian cap of

revolution (illegal to wear at that time), her knife drawn to kill him

in his sleep as soon as her balance of justice tips.

The

artist of the print, signed with the initials A.C., remains

unidentified. The heading "Caricatures politiques No. 45" tell us that

it was issued as part of a series, and raises the possibility that it

was published by Philipon's press.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cham, [Anarchist Bookshop] Études Sociales. 1848. Lithograph. Bureau de Charivari: Paris. Printed by Aubert & Co. 8.75" x 10.75".

Although the satirical magazine

Charivari (see other issues held

by the Revenant Archive) was a major force in the anti-Monarchist

opposition, it stopped short of endorsing the most radical political

positions held by Anarchist, Communist and other extreme socialist

activists. Though its efforts were focused against the Orleans monarchy

until the revolution of 1848, during the short-lived Second Republic its

barbs were thrown both right and left, against ideologies which were

receiving wide-spread consideration for the first time––a state of

affairs which would soon end with the totalitarian coup d'état of

Napoleon III in 1851.

This

must be one of the earliest depictions of an Anarchist

Bookshop––produced within months of the 1848 Revolution, before which

such subversive literature was quite dangerous to circulate in France,

and only eight years after the

movement's principal theorist and promoter, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, became the first

self-proclaimed "anarchist." It is a simple stand selling various

tracts about anarchist economics and politics, its signage reading:

PROUDHON REPAIR [misspelled] OF ALL KINDS RESTORED THE OLD TO NEW.

The proprietor is clearly a cobbler by trade, and, we are meant to

infer, semi-literate––an insult to Anarchism's working-class adherents,

many of whom were self-taught. The customer, on the other hand, is an

eighteenth-century aristocrat, possibly a parody of the movement's more

intellectual supporters. The caption reads: "Reassembly, repair and

re-soling of old political, financial and social systems."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cham, [Proudhon the New God] Études Sociales. 1848. Lithograph. Bureau de Charivari: Paris. Printed by Aubert & Co. 8.75" x 10.75".

Published as part of the same series of anti-Anarchist cartoons as the print above (see description for further context), this

print shows that, for a brief moment between the Revolution of 1848 and

the Bourgeois Liberal crackdown on proletarian radicalism in the

following year, Anarchism enjoyed a certain degree of popular support.

As mother and child look upon an effigy of the anarchist polemicist

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, they hold the following dialogue:

"Hey, son, there is the new god!..."

"Mom, is he the one who will pull us out of chaos?..."

"No, he is the one who wants to plunge us back in!..."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cham, Candidature romantico-politique d'Eugène Sue (Eugène Sue's Romantico-political Candidacy). 1849. Lithograph. Printed by Aubert: Paris.

The

centrist political cartoonist Cham can often be counted on to provide

early glimpses into marginal and radical movements that are graphically

unrepresented otherwise, even if he usually does so in service of

ridicule (for instance his 1848 image of an anarchist bookshop, also

held by the Revenant Archive). By the mid-1840s, even mainstream

Romanticism was associated with socialism, and a number of prominent

liberal and socialist Romanticists including

Lamartine, Hugo, and Esquiros transitioned successfully into

electoral politics after the 1848 revolution, though most were deposed

and/or exiled (and the rest turned into lackies) in Napoleon III's coup

d'etat in 1851.

The popular novelist Eugène Sue (see his

Mysteries of Paris in this archive under

Literature)

was one of those who made the transition into politics, elected to the Chamber of Deputies; he was exiled for protesting

Napoleon III's coup d'état, dying in Italy. The American Socialist

leader and labour organiser Eugene Victor Debs was named after Hugo and

Sue. Here he is pictured surrounded by his best-known characters, most

drawn from the working or criminal classes.

This

print was part of an unidentified illustrated newspaper, as evidenced

by the adverts on the back, including a large one for a book of

socialist theory.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Victor Hugo. (1828) Intaglio on silk.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

c.1830) Intaglio; engraved by François Monceau.

The myth of Pygmalion and Galatea has been recurrent within the avant-garde—indeed within creative culture generally—since at least the inception of Romanticism, for obvious reasons. 'Romanticism' translates literally as 'Novelism' or 'Fictionism', and the attempt to infuse and change life according to poetic, musical, and artistic principles was the explicit goal of the avant-garde of Romanticism. The pretext for Devéria's treatment is the 1770 play by Rousseau. In addition to Rousseau's general decisive influence on Romanticist philosophy, psychology, and self-presentation, his Pygmalion was one of the very first Melodramas, a form being championed and developed by French Romanticism at the time Devéria was working on the piece. Pygmalion and Galatea was printed in the same year as Devéria helped to organist the Romanticist 'army' that would fight on behalf of Hugo's Romanticist melodrama

Hernani.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Cherub. (c.1830) Intaglio; engraved by Adrien Godefroy.

In Cherub, Devéria fuses Romantic sentimentalism with a faint, weird touch that hints at the unconventional nature of his underground work (today priced far beyond the means of working-class salaries, as part of the niche erotica market). In a scene reminiscent of the Provençal troubadours of the late Middle Ages, a lady listens with apparent suspicion to the song of a cherub. In Cherub, Devéria fuses Romantic sentimentalism with a faint, weird touch that hints at the unconventional nature of his underground work (today priced far beyond the means of working-class salaries, as part of the niche erotica market). In a scene reminiscent of the Provençal troubadours of the late Middle Ages, a lady listens with apparent suspicion to the song of a cherub hovering above her balcony. The apparently innocuous scene has darker undertones; the cherub remains locked out of her apartments, and the downy, dove-like wings of the Cherubs of Boucher and other 18th Century painters contemptuously dubbed 'rococo' by the Romantics have been replaced by the thin, filmy, undersized wings of an insect.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, 11 heures du matin (11 o'clock in the Morning). (c.1830) Lithograph. Printed by Forouge.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, 2 Heures après midi (2 o'clock in the Afternoon). (c.1830) Full colour lithograph. Printed by Forouge.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, 4 heures du soir (4 o’clock in the Afternoon). (c. 1830) Lithograph. Printed by Fourouge.

Devéria

supported, almost on his own, his parents and his five siblings. While

his brother Eugène was one of the best-known and respected Romanticist

painters, the movement remained unpopular and canvas painting could not

offer security to a large family. Nor could Achille's paintings, his

politicized libertine work, or his teaching. In order to ensure a steady

income, he produced innocuous genre and household scenes like these

prints from the series Huers du jour, produced at the same time that

Devéria was also painting melodramatic history paintings, helping to

plan the 'Battle of Hernani', and training a generation of intellectual

innovators.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, 7 heures du soir (7 o’clock in the Evening). (c.1830) Full colour lithograph. Printed by Fourouge.

Devéria was instrumental in developing the first technology for creating affordable colour lithographs in large volume, a development which allowed him to make a living with prints made for the commercial market, while his more challenging work was made in much smaller volume (and is almost never available on the open market). This print seems to be from a color printing of the Heures du jour series, further touched up by hand in watercolor. It is not known who added the watercolor, but it is less likely to be Devéria himself than to be a worker employed by the printer, Fonrouge; such jobs were often worked by lower middle-class women, either in the shop or from home.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Minuit (Midnight). (c. 1830) Lithograph. Printed by Fourouge.

-from Charles Baudelaire, The Salon of 1845:

“But how comes it that no one thinks of tossing a few sincere blossoms, of plaiting a few loyal tributes to the name of M. Achille Devéria? For long years, and all for our pleasure, this artist poured forth from the inexhaustible well of his invention a stream of ravishing vignettes, of charming little interior-pieces, of graceful scenes of fashionable life, such as no Keepsake—-in spite of the pretensions of the new names—-has since published. He was skilled at coloring the lithographic stone; all his drawings were distinguished, full of feminine charms, and distilled a strangely pleasing kind of reverie. All those fascinating and sweetly sensual women of his were idealizations of women that one had seen and desired in the evening at the cafe-concerts, at the Bouffes, at the Opera, or in the great Salons. Those lithographs, which the dealers buy for three sous and sell for a franc, are the faithful representatives of that elegant, perfumed society of the Restoration, over which there hovers, like a guardian angel, the blond, romantic ghost of the duchesse de Berry.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Portrait of Lady Montague. (Undated, c. 1835) Lithograph. from a miniature by C.F. Zincke.

During the interregnum between the introduction of mass printing and the technology for photographic reproduction, one of the most steady jobs for printmakers was the reproduction of other artwork for magazines and journals. Devéria, like his comrade Nanteuil, made many reductions of paintings and prints by other artists to accompany articles on the visual arts for Romanticist journals, as well as for general sale. This portrait of Lady Montague was made by Devéria from a miniature by C.F. Zincke (the name is misspelled on the print), engraved by Villain, and published by an English printer. A colour version of this print is housed in the National Gallery in London. Nonetheless, the subject of the print would not have been indifferent to Devéria, who like many of the Romantics was probably influenced by her work. Lady Montague was an early proto-Feminist and Orientalist writer, who traveled extensively in the Near East during the 18th Century and wrote a number of accounts of her travels, favourably comparing the role of women in Turkish society to that in Europe.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Le Rendez-vous. (Undated, c. 1825-45) Colour Lithograph. Printed by L. Noël.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Le lever / Rising. (Undated, c. 1825-45) Colour Lithograph. Printed by L. Noël.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, La Separation / The Separation. (Undated, c. 1825-45) Colour Lithograph. Printed by L. Noël.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Le Coucher / Going To Bed. (Undated, c. 1825-45) Colour Lithograph. Printed by L. Noël.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Pardon / Forgiveness. (Undated, c. 1825-45) Colour Lithograph. Printed by L. Noël.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Achille Devéria, Les Jeunes indiens. (Undated, c. 1830-60) Lithograph.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gustave Doré, Les Marseillaise. (1870) Etching.

Doré entered the Romanticist community shortly after the dissolution of the Bouzingo group, and was first published largely in journals edited by ex-Bouzingos such as Gautier, Nanteuil, and Nerval. By the 1850s he had become by far the most prominent Romanticist illustrator/illuminator, continuing the tradition of Nanteuil and Boulanger but with much greater recognition and remuneration; a generation younger, he inherited the benefits of the mainstream Romanticism that they had helped to create and then taken leave of. This image is highly charged: It was created in 1870, the year in which German forces ended the 20-year old dictatorship of Napoleon, the radical socialist Commune was established in Paris, and was then suppressed months later with days of mass executions sanctified by the combined forces of Europe. In an obvious homage to Delacroix's painting in response to the 1848 Revolution, a mass of soldiers and citizens advance, with the mythic figure of Liberty wearing the Revolutionary phrygian cap. The title of the etching is allied to the traditional song of French Liberty, which was banned under Napoleon III's regime.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Portrait of Alphonse Esquiros. Unsigned. c. 1843. Engraving.

The

radical activity of Alphonse Esquiros spanned many underground

networks. He was a leading figure in the Romanticist avant-garde,

publishing poetry and fiction in anthologies and journals, and

collaborated with the Jeunes-France / Bouzingo group; initially headed

for ordination, he broke with the church under the influence of

Lammenais and became a notorious anti-clericalist, denounced by the

Church in 1840 after publishing a book presenting Jesus as a social

reformer and proponent of democracy; furthermore, he played an important

role in the french occult revival of the 19th Century, and was involved

with the feminist-mystical Evadamist group led by the Mapah Ganneau,

where he worked with the young Eliphas Lévi, as well as the feminist

union-organiser Flora Tristan; and the self-declared Jacobin was very

active in various socialist circles, both as an organiser and as an

historian of revolution. After the 1848 Revolution, this heretical

occultist experimental poet was, remarkably, elected to the National

Assembly in 1850. He was expelled from France after Napoleon III's

coup-d'etat the following year, and lived in Belgium, Holland and

England for nearly two decades. Finally returning to France, he was

again elected to the National Assembly after the emperor's abdication,

and remained committed throughout his life to the far left.

The

artist and source of this nicely-executed print are unknown. The dating

is based on comparison with the sculptor David d'Angers' 1843 medallion

portrait of Esquiros, which shows him with identical hair, beard, and

even pose, and may well have served as the model for the engraving.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Unknown [Fleury?], Prado. (c. 1840) Lithograph.

This intriguing print is in certain ways quite explicit in its concerns, in other ways very mysterious. On the one hand, the print brings together a great deal of iconography specific to underground, radical Romanticism to present a tableau of the theory of radical friendship known in Romanticist parlance as camaraderie: in the centre we find a cénacle of bearded, long-haired young men in flowing, flamboyant clothing--all expressions of Romanticist subculture--gathered together toasting in a moment of boisterous camaraderie. The time period is vague, and seems to combine elements of the 19th Century with echoes of the Middle Ages (the scholar on the right with an alembic) and swash-buckling Renaissance (the loose-fitting shirt and chap with the van-dyke) in Romanticist fashion. Behind them, music is being played, while in the corner are an artist's palette, books, a globe, a written manuscript, and a pipe (another signifier of Romanticist affiliation).

There is also a sword, leading in the other corner to a battle scene--while by no means incongruous with some strains of Romanticism, it is difficult to tell whether this is meant to connect Romanticism to revolution, to neo-Napoleonic nationalism, or simply to a life of adventure (culture as the new 'battleground' in which glory could be won). And then there is the huge, enigmatic word: PRADO. Clearly, this word--simply "field" or "plain" in Spanish and Portugese--communicated something to its intended audience in a way that was clear, immediate, and visceral to its intended audience of French proto-bohemians, enough to emblazon across the print without further explanation; this meaning has been lost. It is true that the Romantics had an affinity for Spanish culture, and I'm reminded of the red tickets distributed to members of the underground "Romanticist Army" just before the "Battle of Hernani," which were printed with nothing but the Spanish word for iron: "HIERRO," which thus became a French Romanticist catch-phrase.

It would seem that there was an 'artistic' café in Paris in the 1840s called the Prado, which may well have been an important venue in the emerging Bohemian subculture; in Henry Murger's Roman-à-clef on Bohemian Paris

Vie de Bohême, the protagonist, after comparing himself to a character in a novel by the Frenetic Romanticist Alphonse Karr (editor of Les Geupes, in this archive), takes refuge with some spiked punch in a café called the Prado; the café appears only in that scene, and is named in passing as if the reader would already know what it is; the place is also mentioned in 1855 in W.B. Jerrold's book on 'Imperial Paris' (parts of which were written earlier). The stories in Murger's book were originally published in journals from 1845 until 1849, when they were turned into a blockbuster play (later adapted by Verdi) two years later published in book form, and 'Bohemia' as a cultural form gained wide-spread recognition. Certainly, the print feels like a document of the transition from Avant-Romanticism to Bohemianism; though the traces of medievalism and the military association are more typical of the earlier movement than post-Murger Bohemianism, the symbols of actual creative work have been shoved to the margins, putting cheerful carousing at centre-stage as appropriate to later conceptions of Bohemia.

These mysteries are made more difficult by the impossibility of assigning the print a definitive date or author. The seller considered it French, circa 1840, and everything about the style and execution confirm that analysis, but it remains approximate. The signature is largely obscured; the seller suggested "Fleury" which seems right, and there are a number of obscure artists by the name who could potentially have drawn it; but there is scarcely any information on them online, none of which information is particularly encouraging, and none match what seem to be the initial "A" or possibly "A.A." or some other superimposed monogram that precede it. It is likely that, whomever they were, they were a member of a late Romanticist/early Bohemian cénacle that met at a Café called the Prado, and that the characters represented were his friends and collaborators. Beyond that, we await further discoveries to supply a missing clue.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Paul Gavarni, Oh! Undated, c. 1827-32. Lithograph from Le Figaro.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Paul Gavarni, At the Barricades. (1848) Etching reproduced in Illustrated London News, March 18, 1848.

Paul Gavarni was one of the formulators of Romanticist satire, to which the majority of politicized writers and illustrators turned their attention after the July Monarchy consolidated its power in the late 1830s. Gavarni worked closely with the Artiste journal of the Bohême Doyenné group, with fellow printmakers Célestin Nanteuil and Tony Johannot, and most especially on Philipon's Charavari. He also illustrated many popular Romanticist books, including the first edition of Eugene Sue's sprawling anti-clerical novel The Wandering Jew (see "Literature"). This print occupies half a page of an issue of a popular British illustrated newspaper, lifted from the French left-wing journal Reform: an eye-witness depiction of the scene behind a barricade under fire from French troops in the Revolution of 1848, which overturned the July Monarchy and instituted the Second Republic—which would last about three years before the coup d'etat of Napoleon III.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

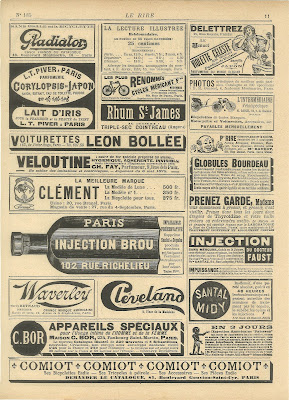

Gyp, La Vérité en marche. Colour lithograph. From Le Rire No. 185, May 21, 1898.

Back.

The Dreyfus Affair, in which the French Army framed a Jewish captain for treason in order to

protect the actual culprits, stretched from 1894 to 1906. In 1898 the realist writer Émile Zola [say:

Em-Eel Zoh-Lah] publicly attacked the government for the cover-up. The resulting scandal forced a

public discourse about anti-Semitism and Jewish rights and instigated gentile intellectuals and

politicians to take frm positions for the frst time, swelling into a popular campaign for Jewish civil

rights. This image, by the antisemitic cartoonist Gyp, portrays Zola and the socialist politician Jean Jaurès, who was later assassinated for his opposition to World War I, springing to Dreyfus' defense.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tony Johannot, Le Jeuf errant (The Wandering Jew). (Undated, probably c. 1844-1852) Intaglio; engraved by Jaubert.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[David?] Merwart, Editorial Breakfast at the Chat Noir. 1887. Etching. From Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Harpers: New York. 9.5" x 7".

Although

the masthead lists Rodolphe Salis and Alphonse Allais as editors, it

also lists Maurice Isabey as "Administrator" and two "secretaries of

direction," who were Georges Auriol and a rotating cast of Chat Noir

habitués (see "Chat Noir" Collection in this archive), plus occasional fleeting editorial positions such as "Musician

of the Future," held by Donizetti in December 1889 and "Always

forgotten," held by Chapsal the same month. In fact, writing and editing

the journal was a collective effort, usually done in the cabaret itself

in informal conditions, as shown in this etching from Harpers. The

back contains a page of text about the Chat Noir cabaret from the

magazine article that it illustrates; the online seller did not make

clear that the print was taken from a disemboweled book; I do not usually buy such pieces.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Gustave Moines, Projet d'uniforme (Proposed Uniform). (Late 1848) Lithograph. Printed by Aubert.

The

Revolution of 1848 ushered in the short-lived "Second Republic" in

France, only to be evaporated again in 1851 when a coup d'état

established the totalitarian regime of Napoleon III. The wake of the

revolution brought many radical, marginalised political struggles into

the public eye for the first time in decades, among them the demands of

feminists. These aspirations, along with the possibility (or myth) of

collaboration of bourgeois liberals with radicals and the proletariat,

were crushed in 1849 when the new Republican government used the army to

suppress a massive working-class demonstration agitating for universal

employment and suffrage. This misogynist satirical print was produced

during that brief burst of radical hope, and ridicules the

notion––laughable to average Frenchmen––that political equality for

women might lead to such 'excesses' as female military units. It is

unknown whether this cartoon refers to a real, specific proposal, but it

is not unlikely; many women had fought on the barricades in the

revolution.

The caption reads: "The female citizens of the

republic demand to be organised into a volunteer mobile army corps and

to be dressed at their husbands' expense. They promise to maintain

perfect discipline and silence... sometimes."

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Moloch, Souvenirs macabres (Macabre memories) from L’Éclipse. 1871 [precise date unknown]. Paris.

(Detail: Below)

The

ironic love of the macabre provided a shared space of the avant-garde

and large portions of pop culture throughout the 19th Century, from the

Frenetic Romanticism of early in the century through the Bohemian

cartoonist Moloch 60 years on, who published these gems called “Macabre

Memories” about skeletons undergoing police brutality, hurling anarchist

fart-bombs, and giving each other douches in the satirical magazine LÉclipse the year of the Paris Commune (exact date is unknown).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Don Juan de Marana. (1832) Etching from Monde Dramatique.

As with many working in the avant-garde, the most reliable part of Nanteuil's income derived from his work for Romanticist journals—sometimes reproducing the paintings under discussion for print (before photogravure processes), other times recording Romanticist plays and other events. This etching for the Romanticist drama journal Monde Dramatique, edited by his close friend Gérard de Nerval, portrays Act V of the premier of the popular Romanticist melodrama Don Juan de Marana by Nanteuil's friend Alexandre Dumas. Dumas had been an original member of the Petit-Cénacle, but had distanced himself from the radicalism of the avant-garde as he came more and more into the public eye. Nonetheless he continued to work with Nanteuil on dramatic productions and elaborate, immersive environments for carefully-planned costume balls, possibly giving his tacit approval to avant-garde interventions at his own events as Hugo had done at Hernani. Nanteuil in fact may have designed the sets for this production, which had been mounted the previous year; I am still endeavouring to ascertain this for certain.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, le Mandiant (The Mendicant). 1835. Lithograph. from Charivari.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Le Monde dramatique (The Dramatic World). 1835. Lithograph. from Le Monde Dramatique: Paris.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Portrait of Théophile Gautier (1838) Lithograph. Galerie de la Presse: Paris. Printed by Aubert.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Portrait of Alphonse Karr. 1838. Lithograph. Galerie de la Presse: Paris. Printed by Aubert. With embossed seal of Galerie de la Presse.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nantueil, Gargantua. (Undated, c.1840–50). Lithograph.

In

this avant-Romanticist “portrait” of Rabelais' medieval satirical

character, Gargantua's head and body has been replaced with a scene of

the industrializing city of Paris as a collapsing colonial vortex

drawing in people and goods from across the world. The skewed

perspective, refusal of illusionistic depth and scale, and the

compositional emphasis on the frame reflect Nanteuil's radicalisation of

medieval aesthetics. The Revenant archive contains a letter by the art

historian and Nanteuil specialist Nathan Chaikin in which he attempts to

locate a print from this run (fortunately, as the print in his own set

of reproductions shows, he tracked down a copy in better shape than

this!)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, De profondes des amours [?]. (Undated, c. 1830-1860) Lithograph, w/handwritten title in pencil, partially inscrutable.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, The Cavern. (1855) Etching from Illustrated London News.

The Bouzingo group spearheaded the micro-community known as Frenetic Romanticism, a fusion of extremist Romanticism with popular Gothic subculture, with which most of the first-generation avant-garde were involved. This print depicts a familiar scene from the gothic novels so dear to Nanteuil and other Frenetic Romantics: in the background, a company of armed bandits divide the spoil of a recent crime; while in the foreground, their families cook dinner and play. This picture is from an 1855 issue of the Illustrated London News; it was probably lifted from a French newspaper and likely illustrated a particular story; though the banditti dividing up their spoils is an image that one sees everywhere in early 19th Century Gothic fiction.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Untitled Image of Angel with Insect-Wings. (Undated, c. 1830-1870?) Lithograph.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, La Charité (Charity). 1861. Etching. From

Le Monde Illustré.

This

etching reproduces the ex-Bouzingo artist Nanteuil's painting exhibited

at the 1861. Though photography was developing by this time,

photographs could not yet be easily and cheaply printed for mass

audiences or in newspapers and magazines, so most paintings were

reproduced and known by most people through etchings; Nanteuil, who was

best known as a print-maker, etched this himself.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Célestin Nanteuil, Jolie fille de la garde. c.1832/c.1920 re-impression. Intaglio Etching w/parchment-paper cover-sheet.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jules Platier, Le Lion Artistique (The Artistic Lion/Dandy). 1842. Hand-tinted Lithograph. Bureau de Charivari: Paris. Printed by Aubert & Co. 8.75" x 10.75".

Dandyism

was a consistent force in European counter-culture throughout the 19th

Century, and its central tenants, albeit usually through different

idioms, continue as central components of the avant-garde lifestyle

today. Beginning in England as a practice of refined fashion

trend-setting, it was taken up by the Parisian avant-garde, theorized

and radicalized by people like Roger de Beauvoir, Barbey d'Aurevilly,

and Charles Baudelaire,

who described it as, "a kind of religion"

dedicated to re-designing one's total experience of self through a

rigorous practice of self-control and public presentation. While some

dandies (also known in Parisian slang as "Lions") continued the more

conservative tradition of subtle refinement in dress and manner, others

combined it with the emerging Bohemian subculture (seemingly inimical to

it) and developed wildly idiosyncratic public personas and esoteric

modes of private life and thought.

This satirical series from which this is drawn was published by the comedic journal

Charivari (see

elsewhere in the Prints and Journals tabs of the archive) at the height

of the first explosion of Dandyist eccentricity, in which Baudelaire

first associated himself with the movement, and ridiculed all of the

many sub-streams of Dandyist subculture. This print represents the

'Artistic Lion' or avant-garde dandy. It has been touched-up to an

unusually rich, glossy colour, using a thick binding medium and process

that have not yet been determined.

The caption reads: "T

he

Artistic Lion: He is long-haired, melancholic and abstracted; yet he is

ugly, scruffy, and vain. His favourite haunts are the galleries of the

Louvre. (Flemish school) He feeds on grain such as lentils, beans. In

the old days he sold strikable matches."

The

monocle was a symbol of dandyism and became a symbol of the conscious,

creative re-writing of the Self, re-appearing consistently among the

Decadents, Aesthetics, Symbolists, Futurists, Expressionists, Dadas,

Surrealists, and others––it is from this tradition that

mOnocle-Lash Anti-Press, publisher of works from this archive under Revenant Editions, takes its name.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Charles Ramelet, Diableries fantastiques (Fantastical Devilries). from Charivari, 1833. Lithograph.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A. Schroedter, La bouteille fantastique. Sept. 1838. Etching. From Charivari.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Napoléon Thomas (aka Napoléon Tom/Thom), The Triumph and Glory of Joseph. (c. 1840?) Lithograph.

Napoléon Thomas (or Napoleon Thom or Napoleon Tom, as he sometimes appears) was an ardent member of the Bouzingo group, and in 1838 exhibited in the salon a portrait of Petrus Borel in 'bouzingo costume'. Nonetheless he remains an extremely shadowy figure; no biographical information whatsoever has been uncovered. The scattered work that I have found online consists largely of Napoléonic scenes (often used at the time as a vehicle of thinly-veiled anti-Monarchism, as in the work of Béranger and Sue), which increases the probability of his name being a pseudonym; aside from a set of illustrations for Sterne, much of the remainder--biblical, historical, or daily scenes--contains text descriptions in both French and Spanish, indicating that he may have left France and thus disappeared from the discourse there; but this all remains speculative. The latest positive datings on his work are in 1840, but many (including this) are undated. This print--a very nice impression on quality paper--is one of a set focusing on various incidents in the life of Joseph. Thomas's primitivist and hieratic figurative approach--which reflects his affinities with other Medievalist bouzingo such as Nanteuil and DuSeigneur--lends itself well to the tradition of Spanish Catholic martyrology-prints and explains his apparent success in spanish-speaking milieus. This print resided in Brazil until I bought it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Napoléon Thomas (aka Napoléon Tom/Thom), Le Vase d'airain (The Bronze Vase). (c. 1835-50?) Lithograph. From the series Album du Journal des Jeunes Personnes.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

No comments:

Post a Comment